Emily Acheson

Medical Geography

Medical geography is considered a sub-discipline of geography and considers how geography can provide insights into human health. Medical geographers often ask questions like “Where and when do diseases occur?” and “Why do we see these patterns?”

Disease ecology and health care delivery can both be studied within this field. The research I do focuses on the ecology of diseases and how climate and land use changes affect the distributions of disease agents (e.g. a fungus that infects people) or disease vectors (e.g. mosquitoes carrying malaria parasites).

Some diseases occur in certain places and not others. For example, malaria is not found on the tops of mountains. Why not? Because the vector of malaria parasites, the Anopheles mosquito, cannot survive around the colder mountain peaks.

Disease distributions are affected by a web of factors as well, many of which can be traced by looking at where infected individuals live. These factors could be a contaminated water source, poor access to medical care, or warming temperatures that now allow for the infectious agent to survive in a new location.

By studying these different factors, medical geographers often try to predict where diseases currently are or will spread to at large spatial scales. These predictions are crucial to warning people about where a disease may be coming from, or where it may soon appear.

Not only can medical geographers discover the factors governing disease distributions, but they can also improve or even save human lives. For example, mosquitoes are forever under study for the infectious agents they transmit, such as those causing malaria, chikungunya, and the Zika virus. These diseases affect hundreds of millions of lives every year and owe the majority of their success to mosquitoes.

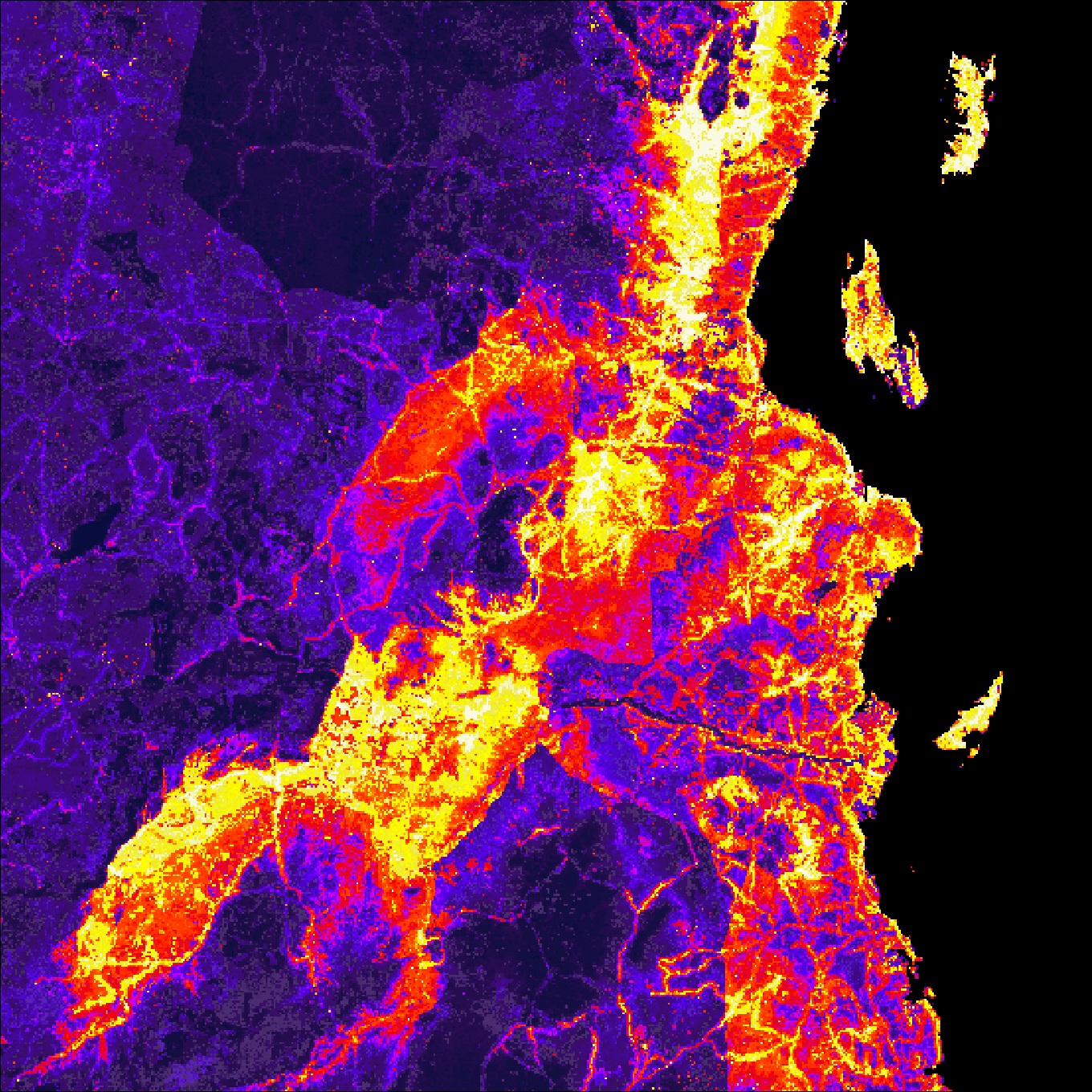

My Master’s research combined the study of mosquito ecology with the study of mosquito net distributions (insecticide-treated nets placed over a bed at night) across Tanzania. My current PhD research is looking into possible factors behind the emergence of a medically-important fungus called Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia. Both of these projects focus on the ecology of the infectious agent or its insect vector, both use geographical tools to try to solve the problem, and both have the goal to prevent further illness.